The Barbie movie so completely portrays the vision of “girl boss” feminism, both in its idealistic form as Barbieland, and its “insert all the corporate messaging approved smash the patriarchy platitudes here” form that at points I didn’t know whether they were trying to parody fashionable feminism or simply so steeped in the corporate zeitgeist - this movie was supposed to be an advertisement of Mattel after all - that those responsible for it didn’t realise just how much of a cliché it was.

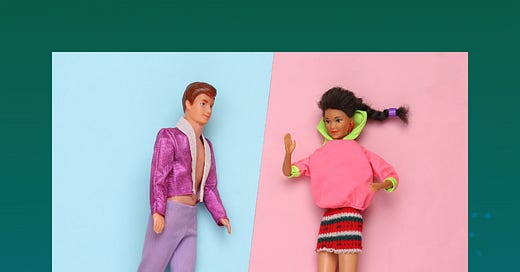

Barbieland: the utopian world of fashionable feminists

Barbieland is a land of “girl bosses” where beautiful, young and unencumbered women rule. This is exactly the type of world that corporate feminism envisions. It is one where no children complicate things - it even portrays pregnant Barbie is an outcast. In Barbieland women are CEOs, Judges, Doctors, Nobel Prize Winners but the blood, sweat and tears required to make it to those positions are never discussed. It is a sexless world where competition between women doesn’t exist – it is girl nights ad infinitum – mostly because the men (“just Ken”) are all incompetent attention seekers who are not worth the time of day and everyone was simply born (or made) to do their prestigious job and didn’t have to ascend anyone else to get their position.

This is exactly the subtext of the ideal of womanhood that corporate feminism preaches. It is all women that are young and without any men or children around that might trump any meaning created through work. There is a lot of talk about women in leadership positions and how to get a female CEO but the question as to who amongst women are willing to put in the hours to achieve that position - and that is not a criticism of women, by the way, not wanting to work 80+ hours a week is more of a sign of sanity than a character flaw in my view. The ideal of sisterhood, where women co-operate rather than compete and the insistence that women will help other women to succeed is taken as gospel despite all women in the workplace having at least one experience to the contrary. The ideal corporate feminist is beautiful, actually the vision of flawless perfection, but not sexual (not least because Barbie doesn’t have genitals).

And on this point, you might permit me a bit of an aside. I usually agree with Jordan B Peterson, but I do contest his wondering whether women wearing make should be banned in the workplace given that blush and lipstick are designed to imitate sexual arousal… but no socially aware woman wears blush and lipstick or “going out to the club” look in the office. For the most part makeup when worn in the workplace plays a “flaw concealing” function (e.g. foundation to hide skin blemishes and neutral coloured lip gloss to hide cracks and dryness of the lips). Women that fail to stay on the beautiful but not sexy side of the line when getting themselves ready in the morning are roundly mocked. One story I heard recently was of a young girl in a law firm whose colleagues gave her a “poor taste award” for dressing too sexy at work events. Women in a workplace typically take cues from each other as to how to dress at work. This means that it differs from company to company (and even on different flaws as was the case when I worked at Macquarie Bank) and enables you to pick where a woman works based on her outfit (which I won’t lie is a fun game to play in the lift in the morning), but also makes the first day in an office the most difficult when the expectations of how to dress as a woman in that particular workplace have not been modelled to you.

The main problem with this vision of womanhood as idealised in Barbieland is that that it will ultimately leave women, who after all aren’t Barbies, unfulfilled. Taking ones meaning in life from things like work and youth is not a recipe for lasting happiness. Very few people – not just women - have careers most of us have jobs. These are merely functions that we fulfill in the productive world that are completely replaceable. There are plenty more lawyers that can be hired to replace me just as there are plenty more people that can be part of a factory assembly line. This is not to denigrate having a job. There is value in being a productive citizen – in fact not having any function that produces something in your life is definitely not a good thing - but that doesn’t mean that it is healthy to base your identity on your position at work.

Not only is this vision of identity based on being a “judge” or “CEO” a terrible recipe for a fulfilling life, Barbieland also portrays the parts of life which provide meaning far deeper than titles and girls night as things to be denigrated. Chief amongst these is the final message of the movie, that Barbie should be just Barbie and Ken should be just Ken. In other words the conflict between the sexes should be resolved by the separation of them not by men and women working together, complementing and enjoying each other.

The Real World: Patriarchy and cliches

The plot of the film – to the extent there is one – is that Barbie and Ken go on a journey from Barbieland to the real world which results in Barbie bringing her owner back to Barbieland. Ken on the other hand discovers that men have respect (and horses) in the real world and tries to bring the patriarchy to Barbieland. What follows is a whole bunch of the usual clichés and talking points about the plight of modern women as expressed by this speech by Barbie’s now adult owner.

These clichés apparently have the power to de-program women from the patriarchy and Barbieland once again becomes a fashionable feminist utopia. The end.

Barbie and Barbieland: the modern feminine heroes’ non-journey

In this podcast Chris points out the lack of a heroes journey given to the female characters in modern movies. They are all begin perfect, something prevents them from achieving their natural greatness, they overcome whatever corrupting force is responsible for them not being able to access their inherent ability and then they return to being perfect. He cites the old and new productions of Mulan and the new Doctor Strange as examples of this.

The story of Barbie and Barbieland follow this story arch completely. Barbie is perfect, comes in contact with the real world which corrupts her, returns to being perfect but in the real world. Barbieland is perfect, is corrupted by the patriarchy, the Barbies reclaim Barbieland and it returns to being perfect.

Chris says that the fact we don’t have any portrayals of a female hero which usually involves transcending to a better state than the one which they were in at the beginning of the story, is infantilising and tells women that they can’t overcome their current limitations to become better versions of themselves.

I mostly agree with this criticism except that I also think that casting women in typical heroes’ journey story arch roles (that typically are about men) would also not be an authentic portrayal of women. I can’t help but think that the current “non-journey” of women in films is touching on something deeper than simply a desire to tell women that they are perfect as they are. To have female heroes undergo an internal rather than physical transformation is somehow fitting and when we think of the most loved female heroines their journey typically takes a more internalised form rather than going off on a physical adventure like Gilgamesh and returning a changed person. Women tend to grow through their connections and their struggles tend to be interpersonal ones (think Beauty and the Beast, Pride and Prejudice etc).

Weirdly the new type of feminine hero is more similar to very ancient ones that feature women on a physical journey, but that journey is often seem as an obstacle not an opportunity for growth. These stories treat women more like a state of nature and whatever leads her to make a journey is a corruption of that state of nature where the world needs to be returned to how it should be. I am thinking here about the classical poem of Mulan - which both the new and old Disney versions seriously deviate from. In the original poem, Mulan’s journey of going to war takes up very few words, instead the focus is the fact that she went to war and returned to the home to be completely feminine (as indicted by the last image of her brushing her hair). This is a story arch is actually very similar to the ones given to women in the movies now but the clear difference between the two what is considered the state of perfection that is being left and returned to. For the original tale of Mulan it is her role as women in the home for Barbie it is her role in this utopia called Barbieland.

It seems like we are returning to a view of women as nature to be preserved in their role rather than to grow and develop, I am not sure what this indicates for the culture more generally. Whilst it is not as inspiring as feminine hero that undergoes hardships and grows, there is a truth hidden in this new type of feminine journey, a journey of return rather than discovery, which perhaps explains the popularity of films like Barbie.

At least for me, the main issue with the Barbie film is that the state of nature being restored is no utopia. Barbieland is no place I’d actually like to live in.

The classical hero is a flawed person who embarks on a quest for something valuable. It turns into an endurance test with an uncertain ending until the hero triumphs over his/her weakness and returns from the journey with two prizes. One is personal growth towards the best person they can be, the other is some significant gift for the the benefit of mankind or just for some other people if he/she is less ambitious. Or maybe just more realistic.

But don't be too realistic or you will procrastinate instead of starting the journey.

Just do it (with a plan.)

Don't die with your music in you (Wayne Bennett)